Here’s to the Musica Reflected in Me

- Bandifesto

- Mar 4, 2018

- 8 min read

Updated: Jan 2, 2019

Written by Pablo Terraza

The twists and turns of our life stories can’t always be represented through art. Sometimes we don’t see certain major moments of our lives in art at all. Sometimes we see moments in our lives played out before it is made into art by another person. There is value in seeing yourself represented, but there is also value in the unique experiences that you may never see represented in popular culture.

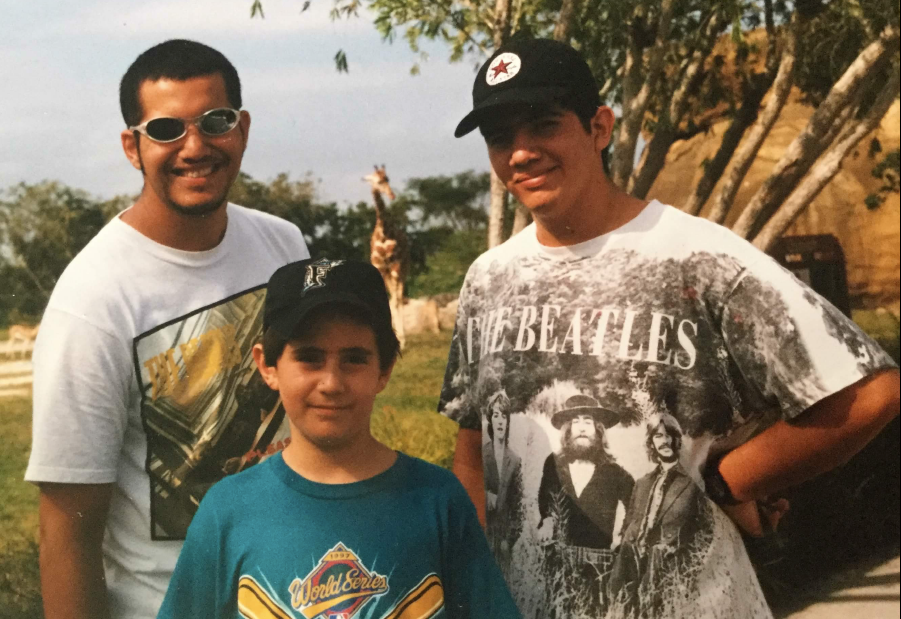

Before leaving our home in Guatemala to immigrate to the United States, my older brothers passed down to me six of their favorite full length albums, recorded from CD format to cassette.

For those familiar with Cameron Crowe’s Almost Famous (2000), a fictionalized drama about the director’s teenage years reporting for Rolling Stone magazine, you may remember Zooey Deschanel’s character leaving home and telling her younger sibling to “Look under your bed; it'll set you free.” Soundtracked by Simon & Garfunkel’s “America,” art reflected my reality, as Deschanel's character passes down her favorite vinyl records to her younger brother as if they were treasured family heirlooms.

In 1998 I lived out this scene so closely that it may have well been just as well soundtracked by two soft voices blended into perfection singing about discovering America. Those cassettes meant the world to me, a then extremely timid ten-year-old boy who felt he could only process popular culture through the guiding ears, eyes and minds of his big brothers, who were nearly a decade older. I clearly recall anxiously sitting in movie theaters alongside them waiting for the end credits roll, so that I could hear their opinion of the movie before sharing my own reflections, which coincidentally would always mirror theirs.

In this moment, art imitates reality. However, the cassettes they chose to leave behind may not be what you expect. Rather than the early Beatles we grew up listening to, or the forbidden Guns N’ Roses’ album, my siblings left me a collection of alternative “rock en español” albums. The music in those albums would prove to be vital in holding on to my Latino roots in the future, and become some of the most personal and seminal albums of the genre to me.

List of albums that my brothers left for me in cassette format. Top left to bottom right.

Hello! MTV Unplugged by Charly Garcia (Argentina, 1995)

El Leon by Fabulosos Cadillacs (Argentina, 1992)

Re by Cafe Tacuba (Mexico, 1994)

Que bonito es casi todo by La Lupita (Mexico, 1994)

Circo Beat by Fito Paez (Argentina, 1994)

Alta Suciedad by Andres Calamaro (Argentina, 1997)

My mom was always proud to tell people that there was and always would be music playing at our house. She would say that she could not “stand” silence. Some families left the television on to fill the void, but ours would enrich the environment with music in an intentional way. This was not random music from the radio, but painstakingly curated selections by my parents. Their massive collection of CDs (purchased cheaply on vacation in the US) included everything from Classical, Opera, Classic Rock (Beatles, Simon & Garfunkel, CCR), Rhythm and Soul (Harry Belafonte, The Platters, Nat King Cole), and Spanish-language Pop/Oldies. There were specific albums for dinner, for our weekly Bible session, for when my mom’s girlfriends would come over, and for when my grandparents visited. Their music collection had been tailored around the idea of making both themselves and their company happy. Us kids were not permitted to play our CD’s in the living room unless it was our birthdays, and when misbehaving, it was often a tactic of punishment to confiscate our CD’s.

Growing up, I was always very curious about people’s music taste, even when I was in middle school. I still remember experiencing my first taste in rejection when I inquired of my seventh grade substitute teacher her taste in music. Much younger than our regular teacher, I felt more comfortable asking her this question after class. Her reply was to tell me that the question was “too personal”. I never imagined that music could be so personal that you couldn’t tell acquaintances about it. I remember feeling shattered by her response, and crying when I told my mom about it. Though I had been already been introduced to music as something “important” or “personal” many years before as a kid in Guatemala, you could say this moment of rejection further helped shape my understanding of music.

Music always had a sacred feeling to it. You would not skip a great song. You would not end certain albums without listening to the whole thing. With some artists, you would allow time and several listens in order to come to understand and love a song or album that perhaps didn’t sound great at a first listen.

In Guatemala, my brothers’ and my musical experiences evolved when cassette recorders came into the picture. We now had the opportunity to copy full-length albums, create mixtape compilations and even record ourselves over the music that we loved. I vividly recall memories of my brothers taking the time to sit down with me, review several albums, and catalogue my favorite songs in order to put them on a cassette; a mixtape made just for me, with the help of my older siblings. Even the experience of choosing the right songs for these mixtapes was a stressful decision for me, especially when I did so with my oldest brother. If I turned down a song he loved, he would ask pointedly “How can you pass on THAT song?!” I would almost always succumb to his pressure, adding songs that I did not like to these mixtapes. The truth is that the majority of the time, I would end up loving these songs after several listens. Music always had a sacred feeling to it. You would not skip a great song. You would not end certain albums without listening to the whole thing. With some artists, you would allow time and several listens in order to come to understand and love a song or album that perhaps didn’t sound great at a first listen.

Every immigrant experiences the difficult balancing process of assimilation. Similar to packing for a long journey, sooner or later, life demands you to “pack” which values, music, and memories will travel with you for the rest of your life. Our relationship with such things evolves through time. Some we take with us for a period of our journey, some end up in a renewed context and some follow us for the rest of our lives intact as they once were.

When you move from another country, you can often hear elders making the recurring passive-aggressive joke of “Ahora se cree gringo” which translates to “Now they believe that they are gringo/united-statestian”. Implying that the younger, more naive person in question is adapting at a much faster pace, willing to cut ties with their roots and can be seen as thinking that they are superior to those who have not assimilated at the same pace.

In hindsight, I’ve come to think that some of those jokes were perhaps only projections of the elder’s understandable insecurities of not assimilating fast enough to the world they brought their children to. Ironically, you learn with time that cutting down some of your roots (values, memories, culture) is a necessary process in order to allow space for the infinite number of new experiences in the new life that you are living. A life in which you are allowed the privilege of learning different versions of happiness that only moving to another part of the world can offer you. Among these are, learning to express basic sentences in a new language, the often awkward process of finding your voice in that language, understanding the historical and political context of the places you move to and having the opportunity to meet new people - some pleasant, and some unpleasant - who come with their own sets of challenges, baggage, and lessons.

It was a validating experience to see an important life experience of mine being mirrored in a United-Statesian movie like Almost Famous. As if life was signaling to me that I was experiencing a universal human moment.

Not only for the similarities in the scene’s older and younger sibling character’s dynamic but also to see my (interest and) little knowledge of English “Classic Rock” validated in its soundtrack with artists like Rod Stewart, The Who, Elton John, Led Zeppelin and Jimi Hendrix.

While being completely unaware of the rich immigrant history and the revolutionary moments that lead to the founding of the country, seeing this movie confirmed some of what I knew about United-Statesian history: The “American Classic Rock” history.

In a stage of my life in which the world felt it had been turned upside down, with little to no knowledge of the English language to relate to the people I was meeting and the overwhelming challenge of having to adapt to a new world, this scene was an incredibly comforting moment to see played out in a movie. As if there was hope that others in this country had also gone through some of my same experience, and if I looked hard enough, maybe I could meet them.

Different generations experienced the same validation of seeing their music represented in other movie soundtracks. Just as millennials had Garden State with its contemporary indie pop and Royal Tenenbaums with its retro United-Statestian rock, those growing up in the 90’s had Pulp Fiction (retro), Reality Bites (contemporary) and Forrest Gump (retro), those growing up in the 80’s had Pretty in Pink (contemporary) and The Big Chill (vintage), and the earlier in 70’s younger generations had American Graffiti (retro) and Saturday Night Live (contemporary). Each of these movies soundtracks summed up either current or older music that the audience’s generation was sure to know and love.

The same pop culture validation has not been given to alternative Spanish music, even in most Spanish speaking movies. The faces of Spanish-language music in the U.S. are represented mainly by a narrow range of artists like Shakira, Enrique Iglesias, Pitbull, Jennifer Lopez, Gloria Estefan and Juanes. So many other artists from countries like Mexico, Cuba, Argentina, Uruguay, Colombia, and Spain would be much more appropriate in representing the diversity in music and backgrounds within Latin American, Caribbean and Spanish-speaking countries. It would be just as inappropriate to say that Maroon 5 is a good representation of “ Rock” because they happen to write some of their songs and play the guitar.

Regardless of whether you are monolingual or bilingual, there are numerous alternate universes of music in other languages unknown to all of us. Just as United-Statestian and British music has influenced so many musicians that are English-speaking all over the world, they have also impacted the music that is made in other languages. Just as there are artists like Radiohead, Arcade Fire and Kanye West whose music in one way or another stem from older, prominent artists like Nina Simone, Talking Heads, Beatles, and the Smiths, there are a number of Spanish-speaking artists who are equally the descendants of that music.

While I experienced validation in one way during that scene in Almost Famous, there is also a tremendous part of my experience that I have not seen reflected in pop culture. Not seeing music in the language I first learned being represented gave me both a feeling of frustration and further intimacy with that music. The music was something I could call my own, like a treasured secret, and even if I wanted to share it with my most open minded English speaking friends, I knew deep inside they would not have a similar potential for connection or at the very least, understand the words and references made in that music. There is value in your unique experience even if you never see it reflected back to you, just as there is value in the universal moments that allows us to connect to each other.

______________

Pablo Terraza is an immigrant from Guatemala living in the Midwest who hopes to hold on to his accent till the day he dies. He will be happy to make you a mixtape and will likely guess two to three songs that you will love. He has a habit of tying every experience to a piece of music. He is well aware that this may all just be a simulation.